|

Kepler and logarithmic calculation Keplers contribution

to this subject is complex, as he was plagued by quite hectic circumstances,

being between 1618 (when he became aware of Napiers invention) and his death

in 1630: -The witchcraft charge

against his mother around 1620 -The 30 year war

started in 1618 -The development of

the subject by other authors (Ursinus, Briggs, Vlacq) in quick succession in

a time with slow international communication. Kepler was under

pressure to complete the Rudolphine Tables, among others by his maecenas

Rudolph II and the Brahe heirs. As a result he was forced into decisions,

that later had to be revised in view of material newly published by other

authors. It must be said, that

Kepler always has been quite open-minded in those revisions, however to

understand both decisions and revisions a detailed analysis is clarifying. Chilias 1624

In this table the

value of sin(α) varies from 0 to 1 as α progresses from 0º to 90º.

The table, newly calculated by Kepler, has those sin values as argument with

a .001 interval. The logarithms given are positive however. As log1=0 thus in

fact the logarithms of 1/ sin(α) are given (see also Fletcher 1945,

p.179). As Kepler mentions in

a letter to Mästlin those new calculations state a value for log sin 30º of

69314.72, where Napier has 69 as the last 2 digits. The same error was

rediscovered by Sang in 1865 when comparing the Napier table with that of

Ursinus (which is also newly calculated).

The frontispiece of

the Tabula Rudolphinae shows on the roof 6 women impersonating the sciences,

of which Arithmetica has a stick in her left hand and another one in her

right hand of half lengh of the first, being the sides of a triangle relevant

for the calculation of sin 30º=0.5.The correct value of log sin 30º is shown

around her head. This curious detail does not fully apply to those tables

however, as the logarithms included are in 5 digits and the difference thus

does not show anymore. Another novelty

relates the proportions of 1 expressed in the argument column to the

corresponding value in hours, minutes and seconds/24 hours (column 3) and in

minutes and seconds/ degree (column 5). Those logistic values are of

particular use in astronomical calculations, and the further development of

this novelty in the TR must have been a major cause for the use of Keplers

tables for astronomical applications until the end of the 18th

century. Tabulae Rudolphinae 1627 The major part of

those tables is of astronomical nature, describing the motion of the sun,

moon and planets, the latitude and longitude of major cities and other basic

astronomical data. The beginning 23 pages

also give logarithmic values to ease the astronomical calculations using the

astronomical data on the later pages. It is important to be

aware, that the TR are a kind of root-tables, enabling the calculation of

annual Ephemerides, being the positions of the sun, moon and planets in terms

of actual date, time and location. The statement sometimes found, that those

logarithms have been used calculating the TR therefore is at least

incomplete, and possibly not correct. The largest part of

the logarithm section is taken by the first table titled Heptacosias

Logarithmorum Logisticorum, elaborating the concept introduced in the Chilias

of directly supplying logarithms of logistic values. Those are newly

computed, opting for intervals more appropriate for logistic values than the

.001 interval of the Chilias. In a separate table

the logarithms of sin(α) are given at a 1’ interval

(0º<α<90º) at 2 decimals less than in Napiers table. As a result

Kepler could prepare this table from that of Napier, as the error discussed

in the preceeding paragraph vanishes in the rounding. Some minor specifics

of the last decimals show, that Kepler actually used values rounded from

Napier in this table, as is illustrated by the following values of log sin:

Separate tables are

given for the logarithms of cos and tan at ranges and intervals appropriate

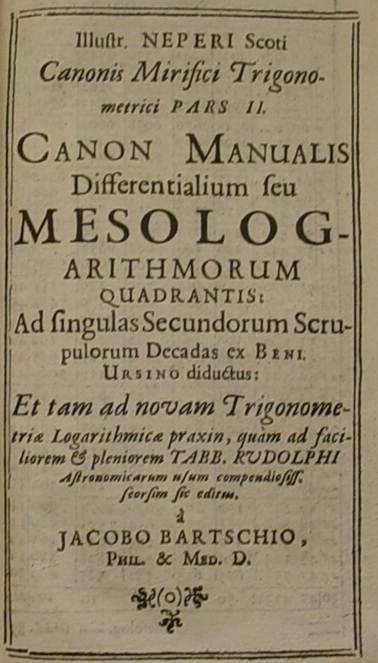

for use in astronomy calculations. Appendix Bartschii 1629

Bartsch completed his

appendix in 1629, and it is not present in most copies of the TR. The

following quotes come from the more complete GW. Bartsch is more practical in

advising his users on supplementary material being available in the meantime

as follows: Si vero laborem…

cupit, substituere potest Ursinus (1624), uso magno, exactissime ad dena

secunda descriptum, aut meos manuales, ex eodem cum ipsius venia derivatos,

qui paucioribus pagellis compendiose descripti,…(If it is required to work

more exactly, it can be replaced by Ursinus (1624), which is extremely useful

and at a 10 second interval, or by my Tabulae Manuales , which are extracted

from the work mentioned last with permission, and which in less pages

describe the matter in a more condensed way,..) GW X 267. Hammer states in his

Nachbericht to Keplers Gesammelte Werke (X p.51*): Without any doubt Kepler

would have been of great service to his users, in case he had decided to use

logarithms of the Briggsian type in the TR. The issue of the Kepler Heptacosias

fivefold enlarged by Jacob Bartsch in 1700 than would not have been

necessary. Bartsch and Hammer

touch on three items here, of which the significance possibly becomes more

clear, when they are dealt with seperately: Briggs 1628 Possibly Hammer is right,

however in practice this option has never been open to Kepler. Hammer himself

states (GW X 21*) that the manuscript of the TR was largely finished in

middle 1624. Briggsian logarithms of trigoniometrical functions only became

available in 1628. Ursinus 1624 Benjamin Ursinus

assisted Kepler before 1620. His Magnus Canon became available in early 1625

(the dating of the intro paragraphs), and states the logarithms of

trigoniometrical values at 3 decimals more (see above) than the TR and at a

10” internal (TR 1’). This is too late to be taken into account in the text

of the TR, completed in manuscipt in

mid 1624. The Bartsch Appendix is from 1629 however and thus can mention it

as very well supplementing the more concise logaritmic section in the TR. Also Kepler has shown

to be quite welcoming to the Magnus Canon. Ursinus owned a copy of the 1627

Kepler tables (the Honeyman #1800 copy. Owen Gingerich states that it was

acquired by the Adler Planetarium in Chicago) warmly inscribed to him, Kepler

calling him and Tycho Brahe "the scientific fathers of those

tables" (my free translation of the Latin text). As Brahe (died 1601)

contributed much to the underlying astronomical observations, for Ursinus

this remark must refer to his log tables. The provenance of our

copy of Ursinus (1624) includes the major astronomer Franz von Zach, whose

activities culminated around 1800. 175 years after publication his interest

in the book can only be understood in connection with the TR. Bartsch and Kepler

could recommend the use of Ursinus (1624) because it avoids the error in the

last 2 decimals of the Napier table, and even adds one other decimal. Bartsch, Tabulae

Manuales 1700 The significance of

this title is twofold. It summarizes Ursinus (1624) omitting the last 3 decimals, however

maintaining the 10” interval, it enlarges that of the TR. On the other hand it enlarges the Heptacosias table

fivefold, the area being of special importance for astronomical calculations,

because of the direct link of logistic values to its logarithms. Maybe this is the

major explanation of the continued use of the triad TR/Magnus Canon/ Tabulae

Manuales for 175 years, combining the astronomical data of the TR with the

most complete trigoniometrical logarithms of the Magna Canon and the smaller

interval of the Heptacosias in the Manuales. Indeed Bartsch did

complete the Tabulae Manuales at the time of his writing the 1629 Appendix to

TR, however the edition (Sagan, 1631) misfired, Bartsch dying short after its

publication, and only 2 incomplete copies (Koenigsberg and Bonn) are known

(see also Caspar 85) to survive. In 1700 Eisenschmid (a

Strassbourg mathematics professor, † 1716) corrected and republished the

Bartsch tables and added a new 9-page Praefatio. Such a reissue after 69

years can only be understood as an appreciation by contemporary astronomers

of the extension of the Heptacosias given. Evaluation

Purely from a calculus

point of view the Heptacosias in the Manuales and the logarithmic values of

trigoniometrical functions in the Magnus Canon are necessary additions to the

TR in their use for astronomical calculations, as is illustrated by their

recommendation by Kepler and Bartsch, the reissue of the Manuales as late as

1700 and the presence of the Canon in the library of Von Zach (*1754). This

makes the TR themselves less interesting within a calculus-oriented

collecting scope. Catalog

For Manuales see 33615 and for the Ursinus’ Magnus Canon 23462.

[023462]

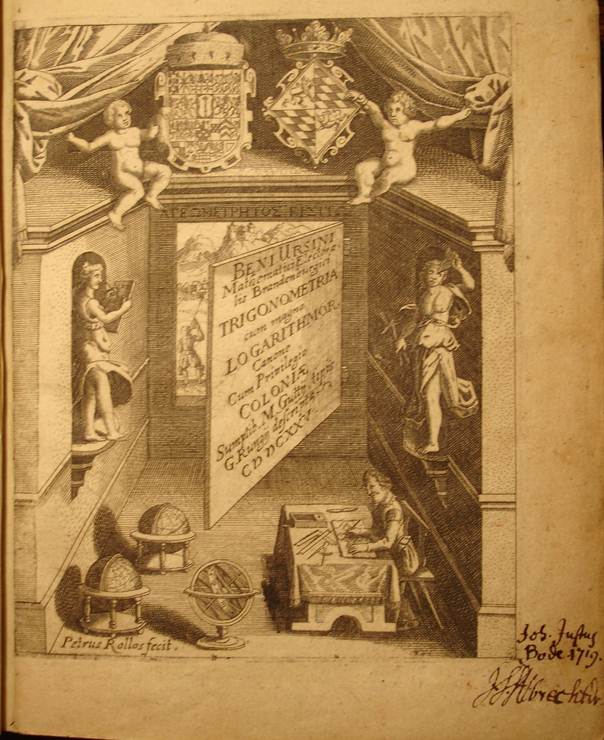

Ursinus, Benjamin. TRIGONOMETRIA CUM MAGNO LOGARITHMOR. CANONE. Colonia: Georg Runge for Martin Gutt, 1625. First

Edition. COLLATION 4to [193*155 mm]. The 2nd part (the Canon) with a seperate

titlepage: Benjamin Ursinus, MAGNUS CANON TRIANGULORUM LOGARITHMICUS,

Colonia, Georg Runge for Martin Gutt, 1624. (4), 272, (454) pp. The 1st.

unnumbered page is the engraved title marked: Petrus Rollos fecit, the title

being on a swinging door in perspective, also described by Henderson, most

likely using the Oxford copy. Also the typo he describes (Guttij tipys) can

be found on this page. The swinging door is earlier seen on Salomon de Caus,

Les raisons des forces mouvantes, Frankfurt, Norton, 1615 (offered by

Interlibrum 253/36). The last leave has errata and a colophon dated 1624 on

the verso. The 2nd title with blank verso, thus 225 leaves remaining for the

tables (5 leaves per degree). All quires in 4, last in 3. Leave 2 and 3 are 1

sheet however, folded at spine. Most descriptions give 227 leaves for the

Canon, Macdonald (p. 158) however mentions a blank leave Lll4, which he

possibly noted in one of the UK copies. Signatures:):(4 A-Z4 Aa-LL A-Z Aa-Zz

Aaa-LLL

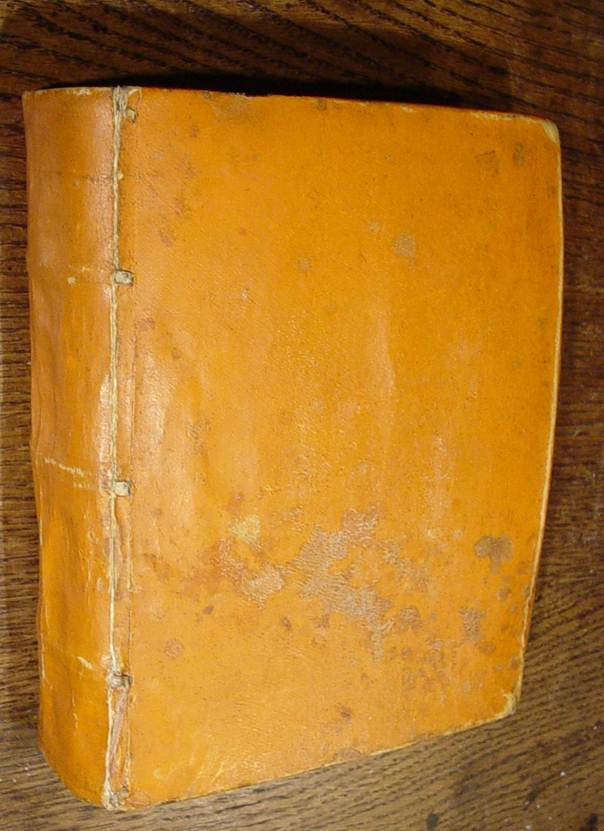

CONDITION Contemporary

overlapping orange (rare in that colour!) vellum (in quite good condition,

taking into account the age). In the past ages the vellum was protected from

the hands of computers by plain paper wrappers, pasted under the endpapers.

Those are now expertly removed. The wrappers are still available in a

seperate envelope, and could easily be reinstalled to a future owners taste.

Edges stained green. Some wear at corners and spine. Pages mildly browned, as

often on books from the 30 Year War period (1618-1648). Contemporary

handwritten expert notes , partly in red. The handwriting of those notes is

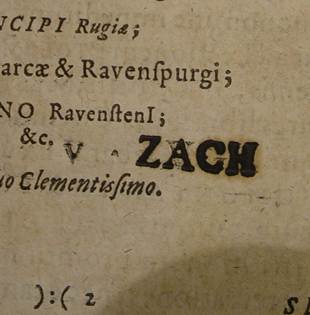

quite like that of Bode's name on title. PROVENANCE Johann Justus Bode, 1719

and "Albrecht", neatly inscibed in the margin of the title. V.

Zach, small stamp on dedication page. JJ Bode (1676-1719) was born in

Bodenburg. He developed a sundial for travelers. The astronomer Franz Xaver

von Zach (Pest 1754) built and supervised the Seefeld observatory for Herzog

Ernst II von Sachsen-Gotha- Altenburg in CONTENTS A copy of the most

extensive table of Napierian logarithms existing. In those log e

(2.302585...) is 1 and not log 10 as in decimal logs used universely since

1628 (the first Vlacq tables). Napier's table (1614) was to minutes in 7

decimals, extended by Ursinus to 10'' in 8 decimals, also giving 1st

differences. The tables have the following main columns: natural sines, log

sines, log tangens, log cosines and cosines, each with a D(ifference) column

behind it. As sin x=cos(90-x) the table runs to 44.59' 50", higher

values for sin being found in the corresponding cosin column and vice versa.

For easy reference those higher values are indicated at the bottom of the

page, as usual ever since. For some arcs often used even more exact values

are calculated (16 decimals, see p. 139 ff. in the text). Napier's table

essentially consists of interpolations of the "Radical Table "

developed by him (see Constructio 47). In this table the sines develop

geometrically with a factor 9995/10000 and the corresponding logarithms

develop arithmetically by the equal interval 5001.25. However in this

progression a calculating error was made, resulting in logsin 30 ending 69,

were Ursinus gives OTHER MATTERS Colonia is Kolln a d

Spree nowedays part of Berlin. The different dating of Trigonometria and

Canon suggest a Sammelband of 2 seperate issues, also the quires are lettered

seperately. KvK mentions 1 separate table (Dusseldorf) and 3 books as

described here (Cologne, Munster and Regensburg), actual copies possibly

being not all as complete as our copy. COPAC has 3 complete copies (Oxford,

BL and UCL), the collation of Oxford exactly agrees with ours. NCC has 1

complete copy (Groningen), with (autopsy 2/12/03) agrees with our collation

plus the leave Lll4 found by Macdonald in some UK copies. In conclusion, the

works are most likely issued together, an individual copy occurring

occasionally, as with the Vlacq tables. Henderson 8.0, Fletcher p. 439 and

179, Dodson III, Macdonald 157 (including a very detailed collation, in

agreement with the present copy except for a last blank leave Lll4).

Macdonald (1889) also mentions copies in Edinburgh and BNF, which cannot be

traced nowadays (2003). Not in Honeyman (never found a copy?) Quite rare and not often seen in

trade. OCLC adds 3 copies in

the US (US Naval Obs., Clark and Un. Michigan). Leave Lll4 not in standard

OCLC description, in which also collation of signatures (identical to our

copy). EVALUATION Fletcher remarks on

those tables (p. 179):" It may be noticed that the 8-decimal Napierian

canon of Ursinus 1624 has never been equalled subsequently." Further Eisenschmid

(the editor of the 1700 edition of Kepler's Tabulae Manuales, see our book

33615, and thus a much more contemporary expert than the present

bibliographer) states, that Bartsch (Keplers son in law and collaborator)

used the Ursinus table, omitting the last 3 figures. Indeed the Tabulae Manuales

are in 5 decimals. As those Tabulae Manuales are an extract of logarithms

from the Tabulae Rudolphinae (1627, which use those logs for astronomical

calculations), those famous Kepler tables are thus (according to

Eisenschmid) based on Ursinus' logarithms! In this connection it

also should be mentioned, that the cos-table in Kepler (1627) has an 10"

interval, which only can come from Ursinus, Napier having a 60"

(=minute) interval. Further Ursinus owned

a copy of the 1627 Kepler tables (the Honeyman #1800 copy. Owen Gingerich

states that it was acquired by the Adler Planetarium in Chicago) warmly

inscribed to him, Kepler calling him and Tycho Brahe "the scientific

fathers of those tables" (my free translation of the Latin text). As

Brahe (died 1601) contributed much to the underlying astronomical

observations, for Ursinus this remark must refer to his log tables. Those observations

support the statement of Eisenschmid concerning the Ursinus source of the

Kepler tables. € 7.200,00

[033615]

Kepler,

Johannes and Jakob Bartsch. TABULAE

MANUALES LOGARITHMICAE. Strassbourg:

Theodor Ierse, 1700. 40, (276) pp. a4-e4, A4-LL4, MM2. 160*95 mm., however

bound in fours. Introduction and 5 tables after seperate subtitles. 19th

century marbled boards with handwritten title on label on spine. 1cm of blank

missing at foot of title. The quite elaborate subtitle is: ad calculum

astronomicum, in specie Tabb. Rudolphinarum compendiose tractandum mire

utiles. Ob defectum prioris editionis Saganensis multum hactenus desideratae.

Quibus accessit in hac editione introductio nova curante Joh. Casp.

Eisenschmid. Kepler's Tabulae Rudolphinarum (folio, Ulm, 1627) were

astronomic tables, in which the tables of logarithms used for its calculation

were also published. The present tables are in a more practical format

(manuales), extracted from them in 1631 by Bartsch (Keplers son in law).

However the edition (Sagan, 1631) misfired, Bartsch dying short after its publication,

and only 2 incomplete copies (Koenigsberg and Bonn) are known (see also

Caspar 85). In 1700 Eisenschmid (a Strassbourg professor, died in 1716)

republished the Bartsch edited tables and added a new 9-page Praefatio. An

important copy of the first generation of logarithms (as we would say in

present day based on the natural number e) dominated by Napier in the UK and

Kepler and Ursinus on the continent. The last 2 also worked together (see

Honeyman 1800, Ursinus copy of the Tabulae of 1627). In 1628 the first

complete version of Briggsian logarithms (based on 10) was published by

Vlacq, and those were used until electronic calculators made logarithms

obsolete around 1978. Henderson 10.1 (see appendix p. 207. Henderson states

12.1, which must be incorrect as 10 are the 1627 Tabulae). 4 copies in COPAC,

|