INTRODUCTION

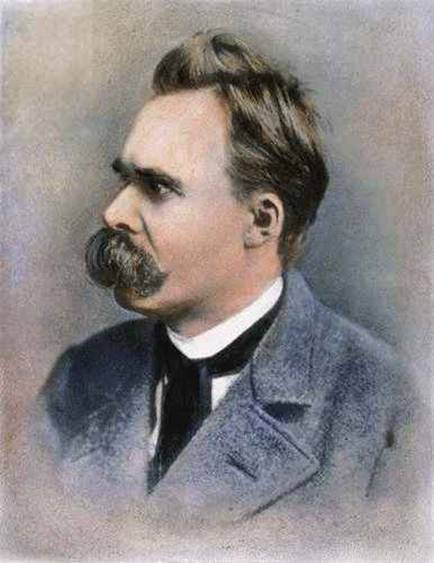

FRIEDRICH

NIETZSCHE

THE MAN AND HIS IDEAS

Because

of his ideas Friedrich Nietzsche is the representative voice of modernity at

the end of the 19th century. Nietzsche revolutionized the style of

philosophical and psychological thought. In the eyes of Freud he is the first

psychoanalyst; in philosophy he thematicized the primacy of language before

Wittgenstein. Finally he is the man who “philosophized with a hammer”, who

exhorted the “free spirits of

This

also is illustrated by the question once addressed to me by J. Dinter: “don’t

you agree that Nietzsche is in fact the end of systematic philosophy?”. Thinking this over on the

But

vice versa Nietzsche takes over, where Wittgenstein ends his Tractatus: Wovon man nicht sprechen

kann, darüber muss man schweigen [Tractatus 7.].

As

Havelock Ellis amends in the introduction to his own book Affirmations [1898] on Nietzsche, Casanova and others: “Yet every

man must make his own affimations. The great questions of life are immortal,

only because no one can answer them for his fellows.”

This

is what in my personal feeling especially my preferred aphoristic Nietzsche is all about.

Not

that this form was a deliberate choice: it has been suggested, that the health

condition of Nietzsche in the years after 1878 did not allow him a span of

thinking longer than that of an aphorism. However this ill health resulted in

many brilliant miniatures, giving a sudden completely surprising new insight,

connection or turn of mind. At the same time showing ironicly the fallacies of

preceeding systematic philosophy and stating a Havelock Ellis type of

affirmation. Having started to read

those aphorisms 40 years ago, I remember quite some moments of laughing, just

from perplexity at the intellectual audacity of this dear paper friend. Such

aphorisms are like a good 20 year old glass of Grand Cru

It

also has been suggested, that Nietzsche adopted the aphorism from the Jesuit

Baltasar Gracian, however in Nietzsche’s work there is no reference to this

author, and his library did not hold a copy of the Oraculo Manual or of Schopenhauer’s 1862 German translation

thereof. So this suggestion should be doubted. If there is any connexion, it

could be indirectly through Schopenhauer.

Finally

it is a small family drama, that in the end, of all

people, his anti-semitic sister Elisabeth tried to put a system into all this.

In addition to his contribution as thinker, Nietzsche was also quite a

remarkable composer.

His

name nowadays is as famous as he predicted it would be, but his influence and

the application of his thought is still a source of real unrest. Still living,

I am sure, he would have quite liked the latter.

This

is my personal affirmation of Nietzsche, the man and his ideas.

Of

course it will prove possible to shoot a nice Nietzschean hole in this short

introduction. Serious attention will be paid only to a reaction of that kind,

if it comprises just a short aphorism.

1882

HIS WORKS

While

Nietzsche´s overall output was large, his books sold very poorly during his

lifetime. Most were issued in an edition of 1,000 copies or less, but none of

his works ever “sold out” in the first edition, first issue state. Therefore

first edition, first issue copies of Nietzsche´s books in any contemporary or

even later binding are considered scarce. For many of Nietzsche´s works, there

are less than perhaps two hundred copies extant with the first issue title

pages.

As

more and more of Nietzsche´s books accumulated in the warehouse, first one

publisher, then another went bankrupt, making it necessary for the works to be

reissued with new title pages (first edition, second issue). For five of his

works Nietzsche prepared new introductions in the futile hope of making his

writings more accessible and more popular. He once stated that those introductions

were the most important texts that ever came out of his pen.

Not

until some years after his mental breakdown in 1889 were Nietzsche´s books

spread all over the world.

It

should be noted at the end of this introduction that I especially thank Bill

Schaberg. His book, The Nietzsche

Canon [1996] made me explore all

those Nietzsche titles and was an indispensable starting point in the

compiling of those digital pages. In addition to this I am grateful to John

Wronoski, H. Blank,

M. F. Burger, J. Dinter, W.

Ritschel, E. von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff and

others for their invaluable guidance in additional research. I further thank

all of them and my wife Margaritha for listening to and commenting on the

exploring views, that necessarily preceeded the final

result presented here.

References are to well known sources. It should be

noted however, that those to WNB are to the digital version of the Weimarer

Nietzsche Bibliographie, available under the heading online-Angebote

at the website of the

Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek in

Nietzschehaus Sils [Engadin

CH]

Remembrance plate on it